Mass Transport: Transport and Transference

This content has been transferred from lacey.se and is not updated for this site yet.

Transport

The performance of a battery depends heavily on the properties of its electrolyte. Total ionic conductivity is one part of this, but how the current is carried by the electrolyte has some important implications, especially when the battery is subjected to very high charge or discharge currents.

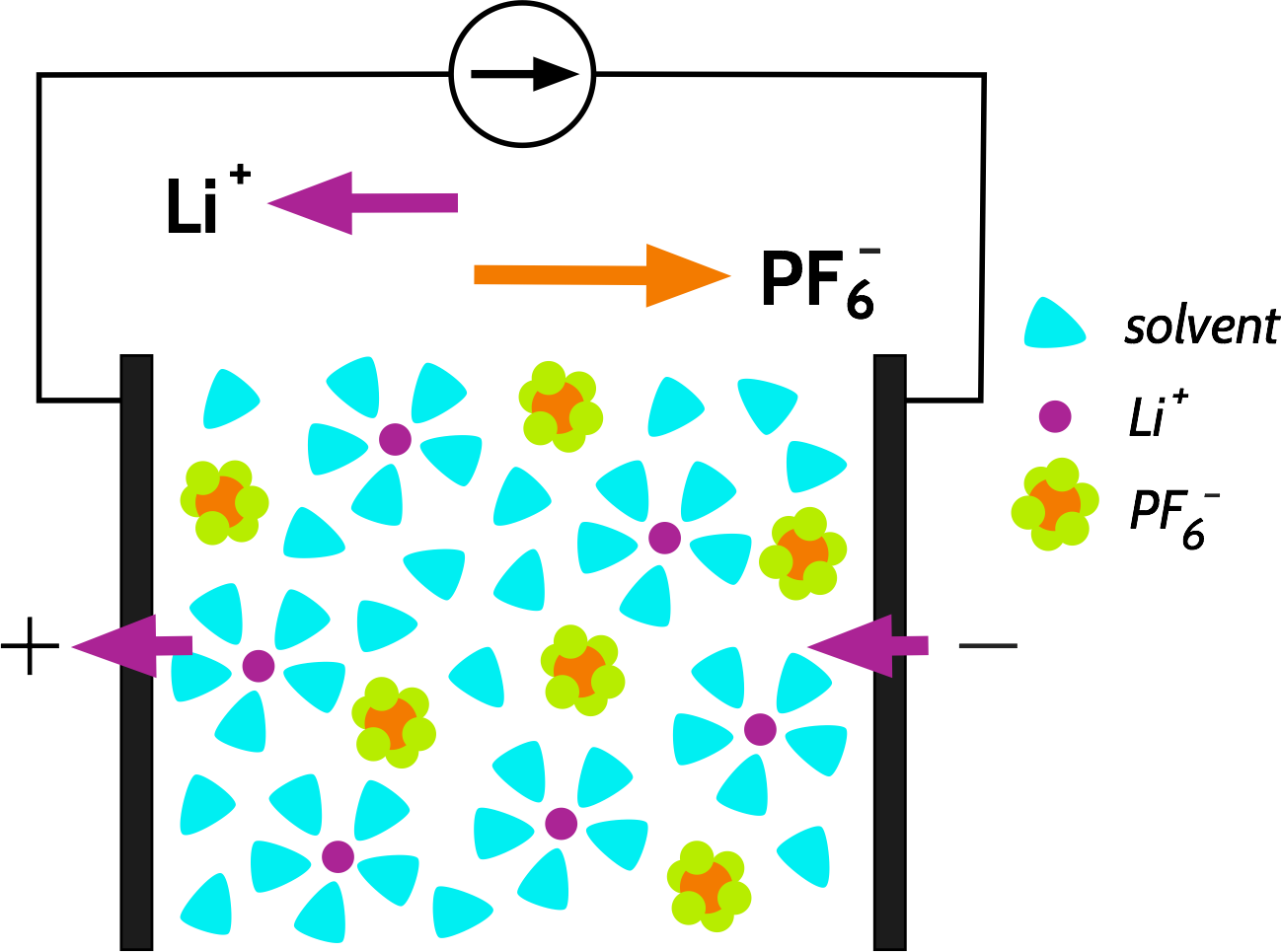

Let’s consider the discharge of a Li-ion battery, containing an electrolyte with a simple salt such as LiPF6, and which is completely dissociated in the solvent. Current is drawn from the cell; Li+ ions are extracted from the negative electrode and inserted into the positive electrode. Part of this current is carried by the transport of Li+ ions, and the rest is carried by the transport of PF6- in the opposite direction:

We call the fraction of the current carried by a specific species, e.g., Li+ or PF6-, the transport number, with the symbol t+ or t_ respectively. The sum of the transport numbers is 1, and by this definition, any transport number for a specific species must be between 0 and 1 (we will revisit this later). A typical value for t+ in a Li-ion battery is usually calculated to be around 0.3.

What does this mean? The transport number is effectively a ratio of the mobilities of the ions, which, following the Nernst-Einstein equation (more on this later) also relates the partial conductivities and the diffusion coefficients to each other:

$$t_+ = \frac{\mu_+}{\mu_+ + \mu_-} = \frac{\sigma_+}{\sigma_+ + \sigma_-} = \frac{D_+}{D_+ + D_-}$$t+ is often smaller than t-, because the non-coordinating anion is often more free to move in the electrolyte, while the “hard” Li+ usually has to drag a large solvation shell with it, or is relatively tightly bound to a polymer electrolyte backbone.

Back to the battery. Because only a part of the current goes into moving Li+ ions, Li+ is consumed at the interface with the positive electrode (or produced at the negative) faster than it is replenished by electrical migration. This creates a gradient in salt concentration in the electrolyte, between the electrodes of the battery. The gradient in concentration then drives diffusion of the salt, which makes up for the rest of the transport of Li+ which isn’t supplied by migration.

The formation of this concentration gradient can ultimately limit the discharge (or charge) of the battery. If the concentration of salt at an electrode surface reaches zero, the ionic resistance becomes huge, and the battery stops. If the concentration of salt becomes too high, the salt can precipitate out altogether, and the resistance can again become huge. (These processes are, however, reversible, in time.)

The value of t+, and the salt diffusion coefficient, determine how fast this concentration gradient forms, and in turn the maximum current that the electrolyte can sustain indefinitely (assuming nothing else is limiting). Both of these parameters are therefore important properties of any electrolyte, in addition to its total ionic conductivity. Ideally, t+ = 1 (and, correspondingly, t- = 0 - implying total immobilisation of the anion). In this situation, a concentration gradient cannot form at all.

Transference, not to be confused with transport

Well, one important consideration, regardless of how carefully the experiment is set up, is that assumption of adherence to the Nernst-Einstein equation. This equation assumes that the ions do not interact with each other when they are dissolved, but this is only even approximately true in very dilute solution, for example concentrations < 0.01 M.

At typical salt concentrations used in batteries - 1 M, or maybe even higher - there are significant interactions between ions. Take a generic salt, LiX, for example. When we dissolve this into a solvent at a relatively high concentration, this dissociates into solvated Li+ and X- ions, but some will remain as neutral [LiX] ion pairs.

We can also consider the potential formation of ion triplets such as [Li2X]+ and [LiX2]-. Whether or not such species really exist is besides the point, but in considering these examples it is clear that the migration of the [Li2X]+ with only 1 positive charge moves two Li+; and the migration of [LiX2]- moves a Li+ in the opposite direction! These each have their own transport numbers. In this case, we should consider the concept of transference, distinct from transport. This is, in fact, the more important concept when it comes to limitations in the battery itself.

The transference number for lithium, for example, is defined as the number of moles of lithium transferred by migration per Faraday of charge. To avoid confusion with the transport number, we will use the symbol T+ (and the transference number of the anion, correspondingly, is T-). It is important to know that transference and transport are often used interchangeably, and usually with the lower case symbol t. However, they are not the same. From the above examples, it should be clear that:

$$T_+ = t_{\text{Li}^+} + 2t_{[\text{Li}_2\text{X}]^+} - t_{[\text{LiX}_2]^-}$$T+ therefore quantifies the net transference of all the Li+-containing species which migrate in the electrolyte. Of course, in an ideal system, where there is no ion association, then T+ = t+.

As with the transport numbers:

$$T_+ + T_- = 1$$However, there are no bounds on individual transference numbers. From the equation above, it is theoretically possible to have T+ < 0 if the mobility of the [LiX2]- triplet is such that it transfers Li+ in the “wrong” direction faster than the other species transfer Li+ in the “right” direction.

That’s not all though: while this is all happening, neutral [LiX] ion pairs - which do not migrate, because they are neutral - are diffusing down the concentration gradient and also, in effect, transferring Li+. However, this is not included in the definition of T+, because the definition of T+ considers only migrating species.

Ultimately, a system could have T+ < 0 and still operate, but diffusion of neutral ion pairs would have to be fast enough to both supply the current passed and compensate for the net effect of migration to transfer Li+ away from where it should be.