Transference number measurement

This content has been transferred from lacey.se and is not updated for this site yet.

For more information about the definition of transport and transference in battery electrolytes, read Mass Transport: Transport and Transference

Measuring t+: the Bruce-Vincent method

The most common experimental method for measuring t+ in a polymer electrolyte is the so-called Bruce-Vincent method, named for the work done by Colin Vincent and Peter Bruce on this subject, published in 1987 (here and here).

The method involves the polarisation of a symmetrical cell (i.e., an electrochemical cell with two Li metal electrodes) by a small potential difference, to induce a small concentration gradient, until the system reaches a steady state, with a concentration gradient that does not change further with time:

This method assumes - as I previously mentioned - that the ions in the electrolyte are perfectly dissociated. More specifically, that the electrolyte obeys the Nernst-Einstein equation, which relates the conductivity (and the electrical mobility) of an ion to its diffusion coefficient:

$$\sigma_i = \frac{\left|z_i\right|^2 F^2 c_i}{RT} D_i$$The derivation of the following equations is long and rather complex (the paper detailing the derivation is 17 pages long), but I will summarise here briefly.

In this case, assuming a perfect system, the current that flows initially depends only on the conductance of the cell and the potential difference $\Delta V$:

$$I_0 = \frac{\sigma}{k} \Delta V$$where $k$ is the cell constant, i.e., the ratio of the distance between the electrodes to the surface area. At steady state, the concentration gradient does not change with time. The migration of the anion is exactly balanced by its diffusion in the opposite direction (that is, the net flux of anions is zero - this has to be the case, because the electrode surfaces are “blocking” to the anions). Meanwhile, the current carried by Li+ is carried exactly 50:50 by migration and diffusion.

The end result of all this is that for very small potential differences (< 10 mV), the current flow at steady state is given simply by:

$$I_{ss} = \frac{t_+ \sigma}{k} \Delta V$$Or, indeed:

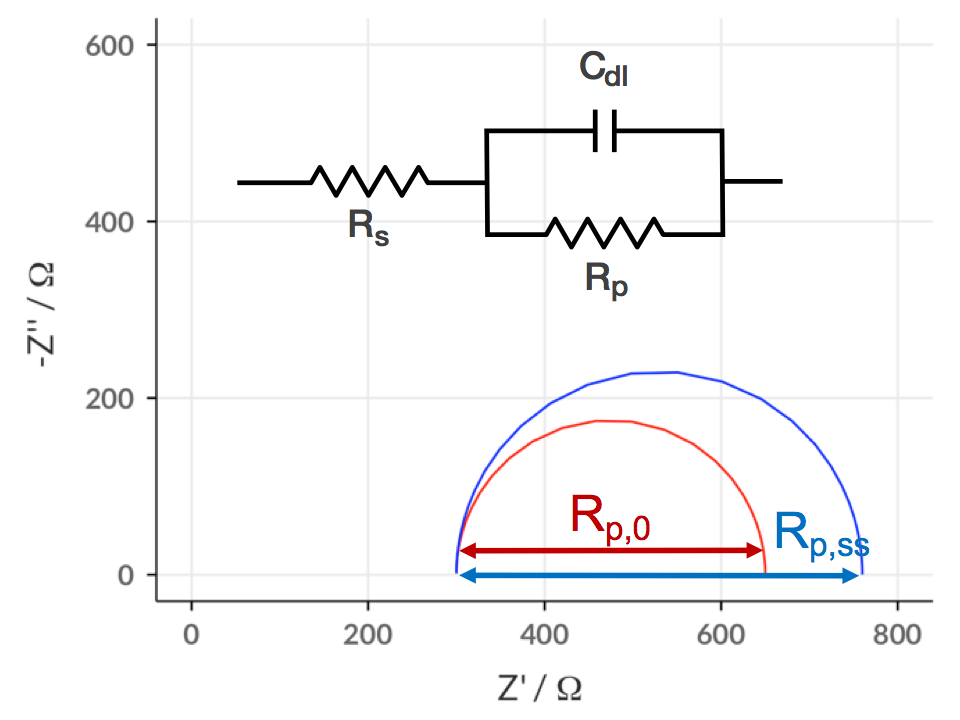

$$t_+ = \frac{I_{ss}}{I_0}$$However! In real systems we have interfacial resistances resulting from surface layers and charge transfer kinetics, so we cannot apply this directly. These resistances may also change with time and concentration. We need to measure the interfacial resistance both initially and at steady state, and ideally the impedance spectra will look something like this:

In this case the series resistance Rs is the ionic resistance of the electrolyte, and Rp the interfacial resistance. Now, the initial current is given by:

$$I_0 = \frac{\Delta V}{k/\sigma + R_{p,0}}$$Correspondingly, the current at steady state is given by:

$$I_{ss} = \frac{\Delta V}{k/t_+ \sigma + R_{p,ss}}$$The expression for the initial current can be rearranged so that:

$$\sigma = \frac{I_0 k}{\Delta V - I_0 R_{p,0}}$$Substituting this equation into the expression for the steady state current gives:

$$I_{ss} = \frac{\Delta V}{\frac{\Delta V - I_0 R_{p,0}}{t_+ I_0} + R_{p,ss}}$$And this ultimately rearranges to give:

$$t_+ = \frac{I_{ss}\left(\Delta V - I_0 R_{p,0}\right)}{I_0 \left(\Delta V - I_{ss} R_{p,ss}\right)}$$This is the well-known Bruce-Vincent equation. Simple, right?!

Determining transference numbers

Because of the assumptions, the Bruce-Vincent method is only valid in very (and unrealistically) dilute systems. So how can we determine the real transference number?

One of the established and reliable methods for calculating the true transference numbers is the Hittorf method. In this case, a known amount of charge is passed through a cell, and the electrolyte is then divided into four or more sections (this is a bit easier with a polymer electrolyte!).

The reason it needs to be four or more is that there must be at least two reference sections where the concentration of the salt are identical to each other. During the passage of charge, migration transfers cations and anions to the electrode surface. If the passage of charge is stopped before a concentration gradient forms in the reference sections, then the transfer of cations and ions into the other sections is due only to migration, and not diffusion. No assumptions about the nature of the electrolyte need to be made!

In this case, there is a change in the amount of salt in section 1 in the diagram above according to:

$$T_- = \frac{-\Delta \text{moles}_\text{Li} F}{Q} $$And therefore, if you can determine the concentration of salt in the sections, you can calculate T- and then, accordingly, T+.

Bruce, Hardgrave and Vincent did in fact use this method in 1992 to show that for a PEO polymer electrolyte containing LiClO4 salt, T+ was calculated to be 0.06 ± 0.05 by the Hittorf method, compared with ~0.2 by their own Bruce-Vincent method. This result showed clearly how the transport of neutral ion pairs and/or negatively charged triplets can cause an overestimate of the true transference number in the Bruce-Vincent method.

There are conceptually similar methods currently under development based on electrophoretic NMR, which also allow for determination of the true transference number, but these approaches are not yet accessible for most researchers. Also, this method (at the time of writing) has yet to be applied to solid polymer electrolytes.

John Newman and co-workers have also been developing an electrochemical method based on concentrated solution theory which also does not require any prior assumptions about the electrolyte. They have shown that under the same DC polarisation conditions as in the Bruce-Vincent experiment, that for a concentrated electrolyte:

$$\frac{I_{ss}}{I_{0}} = \frac{1}{1 + Ne}$$where $Ne$, the dimensionless “Newman number” is a more complicated term containing the true transference number:

$$Ne = a \frac{\sigma RT \left(1 - T_+ \right)^2}{F^2 Dc} \left(1 + \frac{d \ln \gamma_\pm}{d \ln m}\right)$$To use this method, several things need to be measured: $\frac{I_0}{I_{ss}}$, as in the Bruce-Vincent method; the ionic conductivity, $\sigma$; the salt diffusion coefficient, $D$, which can be obtained from the voltage of the cell as it relaxes after the DC polarisation; and the “thermodynamic factor”, $\left(1 + \frac{d \ln \gamma_\pm}{d \ln m}\right)$, which quantifies the concentration dependence of the activity of the ions, and can be obtained from measurements on a concentration cell.

This is a lot of things to measure, and there are different errors associated with all of the measurements; so the overall determination of T+ is subject to significant experimental error. Nonetheless, Pesko et al. have recently used this approach to demonstrate that T+ becomes negative in highly concentrated PEO:LiTFSI polymer electrolytes.

What does this mean for the Bruce-Vincent method?

The Bruce-Vincent method is so convenient, and has become so widely used in the polymer electrolyte research area, that it has effectively become a standard technique used in most reports on new materials. Because of this, there are probably a lot of researchers - maybe even most - using it without fully understanding it.

This is especially relevant now, where a lot of research effort is directed towards, for example, electrolytes with very high salt concentration - where we are a long way from ideality and transference numbers are very high (or so it would appear)! This is also relevant in systems based on ionic liquids, where there are only ions in the electrolyte, and Li+ transference has to compete with the transference of other positively charged species.

In these cases, clearly the Bruce-Vincent method does not give the transference number, T+, or indeed the transport number, t+ - not least for the fact that it measures processes occurring which are not either of those things.

Bruce and Vincent themselves recognised this was the case very shortly after publishing their method, and suggested in such cases that the result of their method should instead be termed the “limiting current fraction”, F+. I would tend to agree - it surely doesn’t make sense to report some quantity you have measured as being T+ when you know it can’t be.

Is F+ a useful quantity, and what does it mean? Well, this debate is likely to continue long into the future. For what it’s worth, I think it can be a helpful value to allow comparisons between different materials (you would expect in most cases that a higher F+ would be a good thing), and to compare results between different groups.

But, F+, as we saw in the expression for the Newman number before, is a mash-up of several other different properties, and so therefore it doesn’t mean very much in itself. For modelling purposes, it’s hopeless - the real T+ is needed.

The problem is, it’s not easy to get. As appealing as the assumption-free Newman approach looks, I’m cautious: it’s not that much more work, but the errors can get pretty large, the T+ values don’t always seem to match up with the Bruce-Vincent method in the very dilute case where you expect they should agree, and I would like to see the results backed up by other methods such as the Hittorf cell or electrophoretic NMR to demonstrate its robustness.

I reckon the Bruce-Vincent method is here to stay, but its users could probably do the field a favour by not calling the result of the experiment something that it isn’t.

Wrap-up

Hopefully this article has been helpful in making sense of the minefield of transference and transport in battery electrolytes. If I would pick out any specific points as particularly important, I would say:

-

There is a difference between transport, t, and transference, T. And they are often mixed up, so it’s a good idea to know how to spot this. Electrochemistry textbooks like Bard & Faulkner discuss transport, but not transference; polymer electrolyte research papers often discuss transference, not transport, but both use small t to denote this. It’s confusing, and I suggest using T for transference to be clear about this!

-

Know what the assumptions in the Bruce-Vincent method are - no ion association (Nernst-Einstein equation is valid), and only applies to very small DC polarisations (< 10 mV).

-

If you know that you have a system which behaves non-ideally (that would be essentially all of them), then consider using F+ instead of T+ to report the results of a Bruce-Vincent experiment.

-

Whoever invents a simple, convenient, accurate method for measuring true transference numbers of both solid and liquid electrolytes is going to be a very well cited scientist indeed.