Cell voltage and the Nernst equation

On this page we’ll look at the origin of cell voltage using a classic battery system, the Daniell cell, as an example. We’ll look at the concepts of redox couples, standard electrode potentials, and the Nernst equation, and predict the discharge voltage curve for the Daniell cell.

Half reactions

Let’s start with a very simple example of a battery: the Daniell cell. This battery uses a negative electrode of zinc metal, immersed in a solution of a zinc salt, and a positive electrode of copper metal, immersed in a solution of a copper salt. Between the electrodes is a porous separator, which also separates the two salt solutions, but allows the transfer of ions between the two electrodes. A schematic of the Daniell cell is shown below.

If there is no external electronic connection between the electrodes, there is an equilibrium between the metal and the ions in the electrolyte, which we can write as a half reaction, in which the metal is the reduced form, and the dissolved ion of that metal is the oxidised form. Any pair of corresponding reduced and oxidised species is referred to as a redox couple. For each redox couple, there is an associated electrode potential, which describes the relative power of the reduced form to act as a reducing agent; that is, its tendency to release its electrons to become its oxidised form. For the Daniell cell, we have the following half-reactions:

At the negative electrode: $\ce{Zn^{2+} <=> Zn + 2e-}$, with a standard potential of -0.34 V vs SHE.

At the positive electrode: $\ce{Cu^{2+} <=> Cu + 2e-}$, with a standard potential of +0.76 V vs SHE.

The word “standard” is very important here. “Standard” means “measured under standard conditions”, which is defined as 1 mol dm-3 of dissolved species in aqueous solution, 1 atm of pressure, 25 °C. SHE means “standard hydrogen electrode”, which is the universally accepted “zero” against which standard potentials are measured. In practice, we’re usually not dealing with standard conditions, or standard electrodes, and we will deal with the consequences of this later.

The lower standard potential of the Zn/Zn2+ redox couple compared to the Cu/Cu2+ redox couple tells us that Zn metal is a stronger reducing agent than Cu; in turn, this tells us that Zn will spontaneously reduce Cu2+ ions to Cu metal, releasing energy in the process. We can write the chemical reaction as:

$$\ce{Zn + Cu^{2+} -> Zn^{2+} + Cu} \tag{1}$$Watch:

If we combine the two half-reactions shown earlier, we’ll see that the overall electrochemical reaction is the same:

$$\ce{Zn + Cu^{2+} <=> Zn^{2+} + Cu} \tag{2}$$The overall standard potential for this reaction is the difference between the positive and negative standard electrode potentials, which for this case is 1.1 V.

This tells us that if we connect the terminals of the Daniell cell to an external circuit and discharge the battery, Zn will oxidise to form Zn2+ at the negative electrode, Cu2+ will reduce to form Cu at the positive electrode, and electrons will flow from negative to positive through the external circuit. If the Daniell cell contains Cu2+ and Zn2+ solutions with concentrations of 1 mol dm-3, and is at 25 °C and 1 atm pressure, then the voltage between the terminals will be 1.1 V, minus any energy losses (which we’ll get to later).

The Daniell cell is therefore operating as a galvanic cell, which is converting the stored energy of a spontaneous chemical reaction into electricity. However, we can also force current into the cell in the opposite direction; in this case, it would operate as an electrolytic cell, where energy is required to drive a non-spontaneous chemical reaction. This process would then recharge the battery, where its stored energy can be released in the galvanic reaction at a later time.

Nernst equation

Once we start passing current through the Daniell cell, we start moving away from standard conditions. One of the most fundamental equations in electrochemistry for calculating electrode potentials is the Nernst equation:

$$E = E^\plimsoll - \frac{RT}{nF}\ln Q \tag{3}$$In this equation, the electrode potential $E$ depends on the standard electrode potential $E^\plimsoll$ and the reaction quotient, $Q$. The reaction quotient is the product of the activities of the reaction products divided by the product of the activities of the reactants. We can write the Nernst equation for the complete Daniell cell like so:

$$E = E^\plimsoll - \frac{RT}{nF}\ln \frac{a_{\ce{Cu}}a_{\ce{Zn^{2+}}}}{a_{\ce{Zn}}a_{\ce{Cu^{2+}}}} \tag{4}$$By definition, the activities of the pure Zn and Cu metals are 1, and we can approximate the ratio of the activities of the Zn2+ and Cu2+ species by the ratio of their concentrations. We can therefore re-write the equation as:

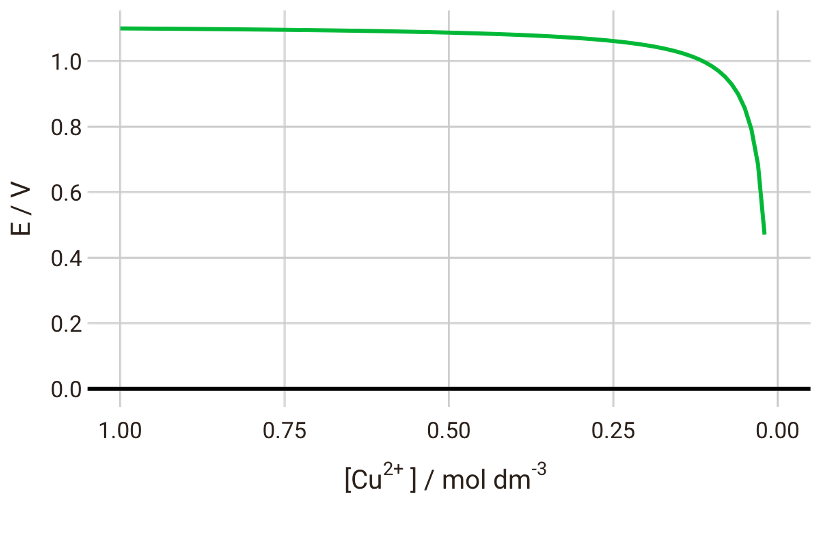

$$E = E^\plimsoll - \frac{RT}{nF}\ln \frac{\left[{\ce{Zn^{2+}}}\right]}{\left[{\ce{Cu^{2+}}}\right]} \tag{5}$$If we plot the cell potential vs the concentration of Cu2+, we will see that the potential gradually decreases until we have almost completely depleted Cu2+ in the system:

With the Nernst equation, therefore, we can predict the discharge voltage curve for this battery system.

Selecting electrode materials for batteries

Tables of standard electrode potentials for a huge variety of redox couples can readily be found on many websites (e.g., here) or in textbooks. In theory, any combination of two redox couples may form the basis for a battery. For example, we can find from the table of standard potentials that lithium (Li) has an extremely low standard potential of -3.01 V vs SHE, which tells us it is an extremely potent reducing agent (i.e., it really wants to be Li+). Similarly, we can find that fluorine (F) has an extremely high standard potential of 2.88 V vs SHE, which indicates that the oxidised form, F2 gas, is a very potent oxidising agent (and really wants to be F-). In principle, this would tell us that a Li–F2 battery has a theoretical cell voltage in the neighbourhood of 5.89 V, much higher than the Daniell cell. However, these numbers on their own don’t tell us much else about the properties of this combination as a battery - its rate (power) capability, rechargeability, safety, and so on. We will learn more about these factors as we continue through this guide.